LESSON 7

![]()

VALIDITY

7-1 Validity

Primary objective of most epidemiologic research - obtain valid

estimate of an effect measure of interest.

In this Lesson

·

Three general types of validity problems

·

Distinguish validity from precision

·

Introduce term bias

·

How to adjust for bias.

Examples of Validity

Problems

Potential problems with studies

· Imperfections in

study design

· Imperfections in

data collection

· Imperfections in

analysis

No imperfections = Valid

Imperfections = Bias

Bias results in distortion of results

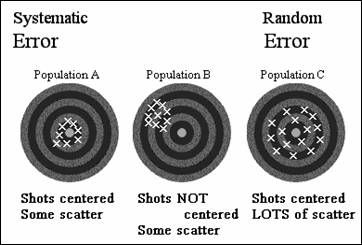

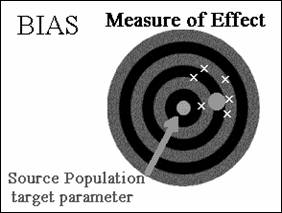

Validity versus Precision

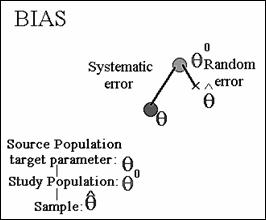

Validity & precision - influenced by 2 different errors

·

Systematic error affects validity

· Random error affects precision.

Valid = No systematic error (i.e., unbiased)

The bull’s eye usually not known, therefore difficult to determine

extent of bias.

Precision: a lot of spread = poor

precision “imprecise”

little spread = good

precision “precise”

Precision reflects sampling variability.

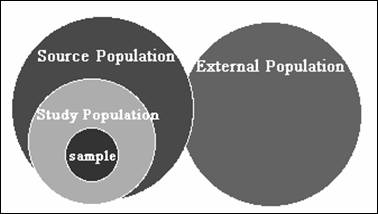

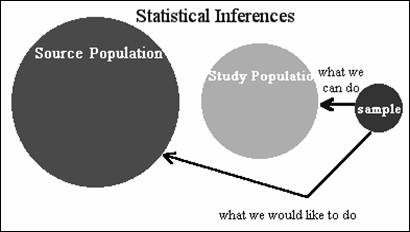

A Hierarchy of Populations

v The sample - collection

of individuals from which study data have been obtained.

v

The study population - the individuals that our sample actually

represents (typically those we can feasibly study).

v

The source population - group of interest about which the

investigator wishes to assess an exposure-disease relationship.

v The external population

- group to which the study has not been restricted but to which the

investigator wishes to generalize.

We would often like to generalize our conclusions to a different external

population.

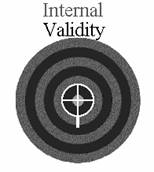

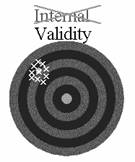

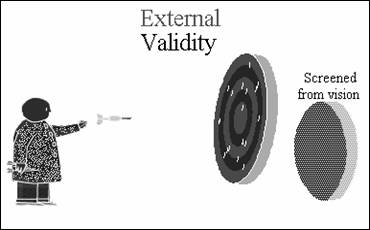

Internal versus External

Validity

Target shooting illustrates difference between internal and external

validity.

· Internal validity considers

whether or not we are aiming at the center of the target. If shooting off target, then study is not

internally valid.

|

|

|

Internal validity - drawing conclusions about source population based on study

population.

External validity – conceptually concerns a different target. We might imagine this external target being

screened from our vision.

External validity - applying conclusions to an external population beyond the study's

restricted interest; subjective, less quantifiable than internal validity.

7-2 Validity

(continued)

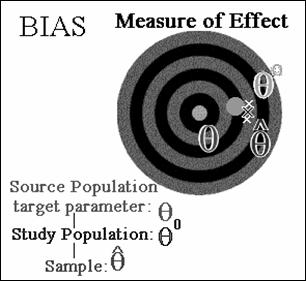

Quantitative Definition of

Bias

A bias can be defined quantitatively in terms of the target

parameter of interest and measure of effect actually being estimated in the

study population.

A study that is not internally valid is said

to have bias.

Target parameter - Greek letter θ (“theta”). We want to estimate the value

of θ in the source population.

θ0 the measure of effect in the study population.

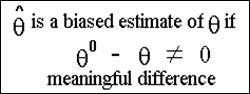

![]() (“theta-hat”) denotes

the estimate of our measure of effect obtained from the sample actually

analyzed.

(“theta-hat”) denotes

the estimate of our measure of effect obtained from the sample actually

analyzed.

Differences between ![]() and θ0

the result of random error.

and θ0

the result of random error.

A difference between θ0 and θ is

due to systematic error.

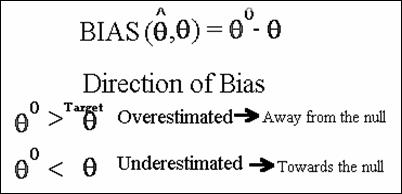

v Bias (![]() ,θ) = θ0 - θ

,θ) = θ0 - θ

The not equal sign should be interpreted as a meaningful

difference from zero.

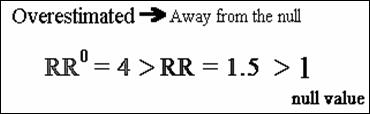

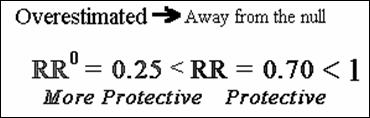

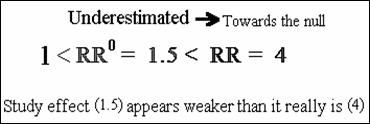

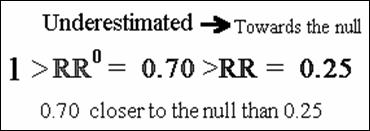

Direction of the Bias

The precise magnitude of bias can never really be quantified,

however, the direction of bias can often be determined.

· The target parameter can be overestimated

(bias away from the null)

· The target parameter can be underestimated

(bias towards the null).

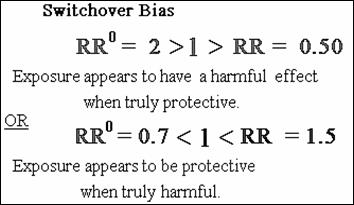

Examples

Switchover bias

Positive vs. negative bias – do not worry about these terms

What Can be Done About Bias?

Three general approaches for addressing bias:

1. Design stage -

minimize or avoid bias. Avoid selection bias by including/excluding

eligible subjects, by

·

Choice of source population

·

Choice of the comparison group

2. Analysis stage -

determine presence or direction of possible bias

Also, account for confounding in analysis.

3. Publication stage -

Potential biases typically described in "Discussion" section. For selection

and information bias, is subjective, judgment expected given inherent

difficulty in quantifying biases.